Alla Povelikhina

Theory of World Unity and the Organic Direction in the 20th Century Russian Avant - Garde

The first quarter of the 20th century was a time of artistic revolution in Russia. In the 1910s and 1920s, Russian artists became the pioneers in the general movement of culture and Russia became the center of philosophical-religious and artistic ideas. There were changes in all aspects of culture in the early 20th century: philosophy, literature, visual arts, and music. French Impressionism and Cubism and Italian Futurism were an enormous external impetus, but then Russian art started basing itself on other assumptions, which for the most part were the Russian traditions of folk art: lubok, signs, embroidery, carving, and toys, as well as icons. By the 1920s artists in Russia had created independent schools and directions. Their variety made Russian art of the period an extraordinary phenomenon.

The “change” in artistic form was created by the break of the positivist, static world perception at the turn of the century, resulting in a profound spiritual leap in the development of society. Art was seen as a component part of world view and world perception. All the major representatives of the avant-garde art dreamed of restructuring the world, of man’s self-perfection through communion with art and through the effect of art on man. Whether this was realistic is another question, but it is important that for the Russian avant-garde, aesthetics alone was not enough. It was to change the world on a new basis. The writer Vasily Rozanov noted, “A new moral world order, that is what characterizes Russian literature.”[1] It was written

about literature, but it held equally for the world of figurative art as well.

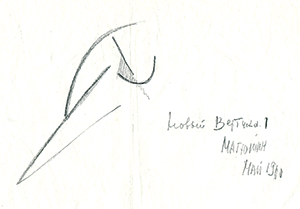

M. Matyushin. New Vertical. May 1920.

M. Matyushin. New Vertical. May 1920.A picture for L. Zheverzheyev’s album l. 269

The Museum of Theatre and Music Art. St. Petersburg

The artist’s vision scheme in different space dimensions.

New Vertical (or New Perpendicular)

is a straight line perpendicular to semicircles

that symbolizes the breadth and

depth of the artist’s space vision.

Matyushin noted that it was «an

escape from deeply understood

three-dimensional space». Boris

Ender wrote in his diary on

September 18, 1920: «Misha’s

[Mikhail Matyushin’s] Vertical is the

first guess and the first attempt to

move from the surface to the earth

body».

It was necessary first of all to bring up the “new man” with a “new consciousness.” The search for universal wholeness, unity, and lost spirituality led to an interest in and study of varied forms of ancient religions, mysteries, and mythology. At the same time, the question of wholeness was becoming central in science as well. There was a convergence of art and science. In the early 20th century, art “broke through” to a new level of mastery of Nature and the Universe, to a new level of vision. There were new criteria of taste, the acuity of which was in dissonance with the traditional concept of beauty of form. Nor was epatage forgotten, either. The center of spiritual and artistic life was the capital of Russia - St. Petersburg.

By the mid-teens certain tendencies were apparent in the artistic avant-garde: Cubo-Futurism, which involved almost all the artists, Mikhail Larionov’s Rayonism, Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism, Vladimir Tatlin’s material culture, and Pavel Filonov’s analytical art. Later Constructivism flourished in Moscow. There was yet another movement in the Russian Avant-Garde, which could be called Organic. The key figures in this tendency were the poet and artist Elena Guro and musician, composer, artist, theoretician, and art historian Mikhail Matyushin. The organic natural source was the principal landmark in the art of Pavel Mansurov; Pyotr Miturich; Boris, Maria, Xenia, and Georgy Ender; and Nikolai Grinberg - students of Matyushin’s studio in the former Academy of Arts in two sessions - 1918-1922 and 1922-1926. In the 1960s this movement was deeply felt and expressed by the artists Vladimir Sterligov (a student of Malevich), Tatiana Glebova (a student of Filonov), Pavel Kondratiev (two years with Matyushin and in the late 1920s and early 1930s with Filonov), and the students of Sterligov and Kondratiev.

The common platform that unites these artists is their world view and world perception, between which in the words of philosopher Pavel Florensky “exists a functional correlation.”[2] Their essence is perception of the world as an organic whole, a world without chaos with a dynamic, self-developing system of phenomena, with definite laws that summarize all the varied parts into a unified whole. In the Organic Whole there is no distinction between small and large, between the micro and the macro cosmos, between the organic and inorganic particles of nature. Stones and crystals grow, and within them, as if all of vegetative nature, there is movement. Growth, fading, death, transformation - there is continual becoming in creative nature. The world is phenomenal and there reality is constantly mutable. These are the underlying assumptions of the Organic world perception, in which the essential quality is wholeness, organic unity with a single order that permeates all of Nature and the Cosmos. “If the life and development of

the smallest resembles the life of the hugest and their essence, i. e., the soul can be expressed in reverse - the smallest bearing within it the greatest - then that means that THERE ISN’T A SINGLE CORR ECT CONC EPT ABOUT APPEARANC ES and all perspectives, physical and moral, are totally wrong and they must be sought anew,” wrote Matyushin in 1912[3]. The whole Organic world view presupposed the synthesis of man and nature, his nondifferentiation from it.

The concept of a world perception as a unity of the whole is not new. One must mention the philosophers Plato and Plotinus as well as the fathers of Christianity, who regarded unity as the highest ontological principle: “The universe is connected into a whole,” wrote St. Gregory in the fourth century. The Organic theory played a major role in European Romantic philosophy in the early 19th century (F. Schelling, F. Schleiermacher, A.W. Schlegel) and Neo-Romantic art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The unity of world view was propounded by the Russian religious philosophers Vladimir Solovyov, Semyon Frank, Sergei Bulgakov, Lev Karsavin, Pavel Florensky, and Nikolai Lossky,[4] who had a great influence on the substance of the spiritual bases of Russian culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The concept of unity did away with the opposition of spirit and nature, idea and action, knowledge and faith. Florensky wrote about this, stressing that in this concept both in theory and in reality the contradictions between idealism and materialism are overcome, but the subordination remains of the material to the ideal, of the world to God.[5] The unity of Nature is not an idea in the human plane, but the very quality of nature, its reality. The geometry of natural forms follows its strict laws. The essence, the inner principle, the character of a thing remain profoundly hidden in nature,

accessible in the artistic plane through observation, contemplation, and intuition, and in the scientific place by fundamental experimentation. The whole worldview presupposes a synthesis not only of man and nature, but of art and science. The artistic genius in his work always reveals the deepest mutual ties of phenomena, comprehending the harmony of the world and creating within the general laws of that harmony.

In the Russian avant-garde such figures as Guro and Matyushin (and with them the poet Velimir Khlebnikov) acutely felt the disharmony between nature and man, nature and creativity. The cult of the machine and technology separated man from nature, divided them. Technicism and machine aesthetics would not give rise to the lost harmony between man and nature. Nature was a primary material, the machine a secondary one.

“The artist now must deep in his ego turn away from all measures and conditions ‘conceived’ from nature, in great privacy, carry and give birth to something as yet unseen and not copied that came into the world through the heavy labor of joyous service to the new incarnation on earth,” wrote Matyushin in 1916.[6] Later he noted that he had been the first “to raise the sign of return to nature”,[7] feeling that the tie to nature was gone, too narrow in the plastic culture of

Cubism.

Through the wholeness of the world view and perception of Guro, Matyushin, the Enders, Miturich, and Sterligov, the representatives of the “organic” direction “returned” nature to us in art itself, in its new plastic image in a new life in paint. We can understand the emotion behind Boris Ender’s statement, “tuning art to return man to nature”[8] The artists of the “organic” movement did not sit with their backs to nature. They did not create a priori plastic paradigms. The basic principle of their behavior was lengthy and attentive observation outdoors - sometimes of the same motif at various times of the day and year. “Staring at material is like a slap in terms of crudity. You can see its essence only in a very slow approach of peace,” Matyushin wrote in his diary. “The eyes are the mailbox of our habitat and they receive a lot of junk and a crumb of truth.”[9] This experience of direct and lengthy observation is experience in the definition of the philosopher Semyon Frank, “living knowledge,” experience in which reality is revealed to us from within, through our own relation to it.[10] This “experience” explains why sketches, studies, and watercolors by these artists predominate over oil paintings.

Following the spirit of comprehension, each of the artists of the “organic” movement managed to see in his own way not the surface of volumes in nature but their interrelationship with one another in the general spatial whole, in the universal connectedness and movement. Before us arises the plastic “portrait” of nature, which holds the most important place in the work of these artists and gives us an idea of their “painting ideology,” in the words of writer Andrei Bely. The works of such artists as Matyushin, the Enders, and Miturich are objectivenonobjective. The synthesis of vision, the penetration deep into the laws of the organic in order to capture the structure of its forms, the interrelation of the forms with one another, the logic of their development, and the influence of light, color, and sound media deform the usual appearance of objects. In the “organic” plastic the whole is not the sum of its parts, but a unique unity of transformed parts. Every shape lives “covered” by the general movement of light, color, mass, and space. Objects become “nonobjective” only in comparison with the old traditional vision and certainly are not abstractions. The shape appearing on canvas and paper was described by Matyushin as the “new spatial realism.”

In order to be able to comprehend the “connectedness” of the organic whole, you have to become co-author of nature, working in accordance with her laws, in tune with her rhythms and sounds, become the tree in the forest and not be an artist with easel on its edge. “Nature tells us - do not imitate me in depicting me. Create the way I do. Learn My Creation. Look at me differently than you have been. In observing you will see the former shape vanish” Matyushin declared about his position on creativity.[11]

Matyushin was the first to see such “arty” objects of nature as roots and twigs, whose shape clearly express movement and growth, i. e., the essence, the origin of the given shape. He seeks that original source in natural forms, he seeks the sign, the archetype. “Any piece of wood - iron - stone -confirmed by the mighty hand of modern intuition can express the sign of divinity much more powerfully than its ordinary passing portrait,” wrote Matyushin in the outline to the article “Path of the Sign” in 1919.[12]

Among the artists of the “organic” movement, Matyushin’s path is unusual. He proposed and expounded his system of perceiving the world, which was distinguished by wholeness and was built on faith in the development of human abilities, both of the body and the spirit. The system was called “ZOR-VED” (an abbreviation of Zrenie, vision, and Vedanie, knowledge). It was an expanded looking.[13] It became the basis of Matyushin’s work as professor at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg (1918-1926), where he headed the studio of Spatial Realism, and as head of the Organic section (1923-1926) at the State Institute of Art Culture, the director of which was his friend Kazimir Malevich.

In the final analysis, ideally Matyushin’s system of self-perfection and his Gestalt psychology of perception were supposed to lead the artist to a new state while observing nature, its elements and spaces. All the work of the Organic Culture section was directed at an experiential confirmation of observation in nature. Here they studied the methods of the artistic language: form, color, and sound in the system of a new approach to the perception of reality. The artist Pyotr Miturich was close in his world perception to Matyushin and his students Boris, Maria, and Xenia Ender. He knew them well personally and often visited the studio of Spatial Realism at the Academy of Arts, Matyushin’s house, and at GINKhUK.[14] His work also opened up a new look at nature. “I am strong in spontaneous observation of nature.

The feeling of beauty and the feeling of truth is that same feeling of nature. Once I realized that, I set myself the goal of developing a ’’new feeling of the world’’ as a necessary cognitive force. On the basis of the combination of dialectical feeling, I sought in images of the observed world new characteristics which I could not find in anyone’s contemporary painting’’[15], -wrote Miturich. Belonging to no single group or school of the avant-garde he found his own artistic language. The main problem in his work is the problem of space. In wholeness, order, and law, in spatial and color harmony he saw as his plastic goal to reveal these hidden and profound characteristics of nature’s Becoming. The “crooked” line of varying thickness and density predominates in his “graphic motifs” (1918-1922) charcoal drawings, playing the role of a natural form-building element. The architectonics of Miturich’s works are derived from natural forms; they grow, develop, and twist at various rhythms and tempos, in contrast of black and white, moving into objective-nonobjective kinetic structures which retain the feeling of the original natural impulse. Those are the principles on which Miturich creates the volumes of his “spatial graphics” (1919-1921) and “Graphic Dictionary” [“Star Alphabet”] of 1919. In “Spatial Graphics the three-dimensional real space is sucked in, enveloping and tying the elements of natural forms (trees, branches, etc.) into a whole, demonstrating on the one hand the indivisibility of Nature, and on the other, its discreteness. Rejecting the diversion of geometric forms, the geometry of the right angle, Miturich felt that only a comprehension of the rhythms of nature and their laws will create a path to the mastery of nature’s infinite and living diversity.

In 1923 the young artist Pavel Mansurov, who had his own path to the ideas of Organica, became head of the Experimental Section of GINKhUK (State Institute of Art Culture). His curriculum for the section included problems that were close to the Organic Culture of Matyushin, whose Weltanschauung was similar to his. “The role of Malevich and Tatlin is visible in my works of 1917, but it was hard for me to free myself of them. Matyushin gave me more with his clear views of things which I would have thought without him but would not have believed completely that I was right,”[16] wrote Mansurov in a letter to art historian Evgeni Kovtun. His program fit the new acute interest in structural forms and laws of nature in connection to the development of natural sciences in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: the creative process had to be based on the study and use of the form-building principles of the organic world. Mansurov derived all the forms of his art from natural forms whose “construction technique” was based on the influences of the environment. The external appearance of plants, animals, and insects bore the imprint of the environment (landscape, local relief, materials, and climate) in which the historical process of their formation took place. True art took the path of nature. “... Our only teacher is Nature. Helping find that teacher, that is teaching people to see Nature - that is the goal of a healthy school,” wrote Mansurov in the article “Against the Academists - Formalists” in 1926.[17]

In the spatial compositions that Mansurov called “Painting Formulas” (1920s) and in the compositions with planetary spheres floating in the paces above the earth there is a sense of cosmic infinity. As Jean-Claude Marcade, the specialist on the Russian Avant-Garde, so subtly noted, their non-objectivity is based on “purification of the tiniest natural rhythms.”[18] The turn to Nature, to the color and form structure of space, is the basis of the work of Vladimir Sterligov - in the 1920s, a student of Malevich. His spatial structures, arising on the painted plane, are tied to the world of natural forms: this is the form-building line, which in spherical space forms a cupola and bowl - a kind of “packaging” of the world. “For the artist, the smallest part of his canvas is the Universe with incidents,”[19] he said.

The universe is perceived by him as a single organism, based on the bowlcupola crooked line structure. In that organism space does not surround nature, but enters it in a new mutual connection, and nature is seen as part of the universe. “...In bowl-cupola art space penetrates the color of space and the color of space penetrates space, and the object (an ancient granny) is not distinguished in any way from the penetrations. Only the penetrations are noticeable,”[20] wrote Sterligov in 1967.

The qualities of a space based on its crisis and qualitative aspects - mobius and topology - bring a new plastic quality of form-building and color to Sterligov’s works. Nonobjectivity in his world carries natural sensation in color and movement of form. “I studied with Malevich and after the square I placed the bowl. As an idea, it is an open bowl. It is the curve of the world, which will never end,” Sterligov said and stressed that “both the bowl and cubism as dimension do not exist. The difference in movement in cubism and bowl is only in the movement of spiritual existence. Without that movement there are only the dimensions left. [...] Time and space are moral phenomena. It makes Form. Has the sky changed? No. It is our perception of it that has changed.”[21]

In art form does not appear in isolation as a rule. Form is not created, form is born. The forms of Sterligov’s work of the 1960s resemble the Western artists Max Bill, Calder, Adan, Jose de Rivera, and Stanislav Kalibal. A French theoretician of architecture, having visited Sterligov’s studio in 1971, wrote, “Sterligov is developing the idea of a new architecture post-Bauhaus, the architecture of ‘a drop of water,’ the architecture of curves embodied in the works of Candela and Niemeyer.”[22]

The artist Pavel Kondratiev entered the Academy of Arts in 1922 and studied for the last two years with Matyushin. When he graduated in 1926, he joined the analytical art group of Pavel Filonov. In the 1960s once again the ideas of Matyushin are closest to his work. “For Cezanne, geometrization is primary, he worked from logic,” Kondratiev said. “Matyushin felt that you cannot force the author’s logic on nature. For the Russian avant-garde the word ‘realism’ was not synonymous with copying nature. The avant-garde can be understood as a new concept of the world.”[23] Kondratiev constantly observed nature finding impulses for his work in it: he sought its inner forms, revealing natural structures and textures worked on the perception of multidimensional spaces. Brought up like Sterligov on the artistic culture of the avant-garde, he found his own “measure of the world.”

The Organic line in the Russian avant-garde art is not complete with the names listed above. As already noted, Matyushin, Sterligov, and Kondratiev had many students and followers, who shared their Weltanschauung and perception of the world and their acute interest in the deep beauty of Nature and the Cosmos. For all the brilliant diversity in the art of these artists, they share general fundamental principles that allow us to mark the Organic, natural movement in Russian classic avant-garde. The main principle is the respect for nature as a possible communion with nature on a higher plane. The Organic movement is one of the historical aspects of a multilevel understanding and artistic expression of a single Truth.

Alla Povelikhina

[2] Pavel Florensky, Opravdanie kosmosa [Justification of the Cosmos], St. Petersburg 1994, p. 31..

[8] Boris Ender, Diary, 1920, Private archive, Rome..

[10] Semyon Frank, Real’nost’ i chelovek [Reality and Man], St. Petersburg 1997, p. 162..

[11] Mikhail Matyushin, Notebook with Notes No. 2 (July 1923), RO IRLI, f. 656 d. 104, p. 73..

[16] “Pavel Mansurov. The Petrograd Avant-Garde”, exhibition catalogue, Rome, 1915, p. 16..

[19] Vladimir Sterligov, Notation in 1971, Private archive, St. Petersburg..

[20] Vladimir Sterligov, Notation in notebook, 1967, Private archive, St. Petersburg..

[21] Vladimir Sterligov, Notation in 1970, Private archive, St. Petersburg..

[23] Pavel Kondratiev, Notation of the 1970s, Private archive, St. Petersburg..